Stan Lee’s Daredevil Begins

Pedal to the Devil

Origins

In the early 1960’s Stan Lee was hoping that the people would see the light, and superhero comics would ramp up in popularity. The likes of Fantastic Four and Spider-Man were captivating the masses, and importantly, their pockets. As outlined in Sean Howe’s Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, Lee was frantically capitalizing on recent growth in the market in an attempt to court both financial stability and overall legitimacy for himself as a writer and storyteller. Perhaps more impactfully he was striving to have those attributes applied to the comics as a medium itself.

Fans of the emerging Marvel universe were as caught up in the names behind the characters, than the costumed adventurers themselves. The likes of Steve Ditko, Stan himself, and certainly Jack Kirby, were attracting readers in an early form of fandom. In an effort to expand past the limited roster of both heroes and creators, Marvel comics began trying out fresh faces both off and on the page.

It would turn out that the faces really only needed to be fresh to the readers for the most part, as a good number of those recruited into the business at this time were veterans of sorts of the comic book industry. Along with himself and Kirby, Lee recruited artist Bill Everett to help with the creation of one of the new superheroes. Leaving right after the debut issue, creation would turn out to be the main contribution from Everett.

Slightly conflicting accounts of the design of Daredevil exist from all three of the regularly credited creators, as described by Mark Evanier on the Jack F.A.Q. at POVONLINE. Suffice to say Lee, Everett, and Kirby all seem to be wholly worthy of a co-creator credit. The full truth is most likely lost to the time, but the seemingly plausible explanation, as told by Marvel Comics’ former editor-in-chief Joe Quesada is that Lee, Everett, and Kirby significantly contributed to the initial character production. Artists Steve Ditko and Sol Brodsky also came in to help at least finish the issue, but their exact contributions have not been reliably expounded on. The starting point for Daredevil is precisely known however, as he originates from a former comics superhero named… Daredevil.

The original Daredevil was a Liv Gleason Publication character, created by Jack Binder in the 1940’s, and was slightly reworked early on by writer and artist Charles Biro. This costumed crime fighter would begin mute, equipped with a boomerang, and wearing a spiked metal belt over his superhero tights. The mute angle would quickly be dropped, and a background of being raised by an aboriginal community in Australia would be established, presumably to explain the boomerang shtick. The modern Daredevil would inherit the concept of a disability, though he would persist being blind, as opposed to his counterpart’s muteness. This, coupled with his evening status of costumed vigilante, were about all the shared crossover from the two heroes besides their moniker.

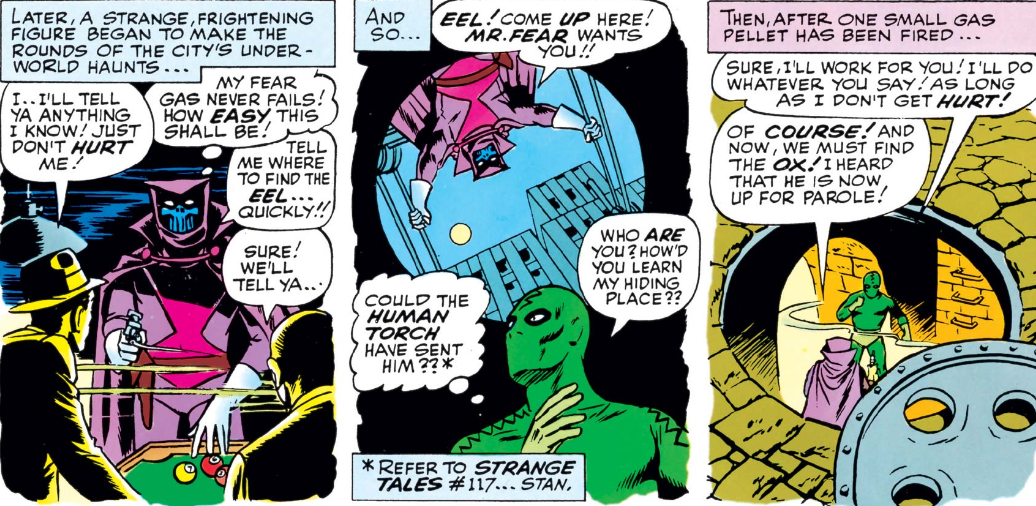

Early on in Lee’s run, Daredevil may appear to rip from the in-house hit of Spider-Man more than even the progenitor of his name. Using his billy clubs to swing around the city in lieu of webs, coupled with the signature quippy nature of Lee’s dialogue, it would take a bit for Daredevil to really break the mold. Many villains would be borrowed or generic, and honestly a lot of early Daredevil feels like it is re-treading ground a bit. As the series develops the relationships between the main characters do shine through, and that is where a lot of the title’s charm is derived.

Nelson and Murdock Attorneys at Law

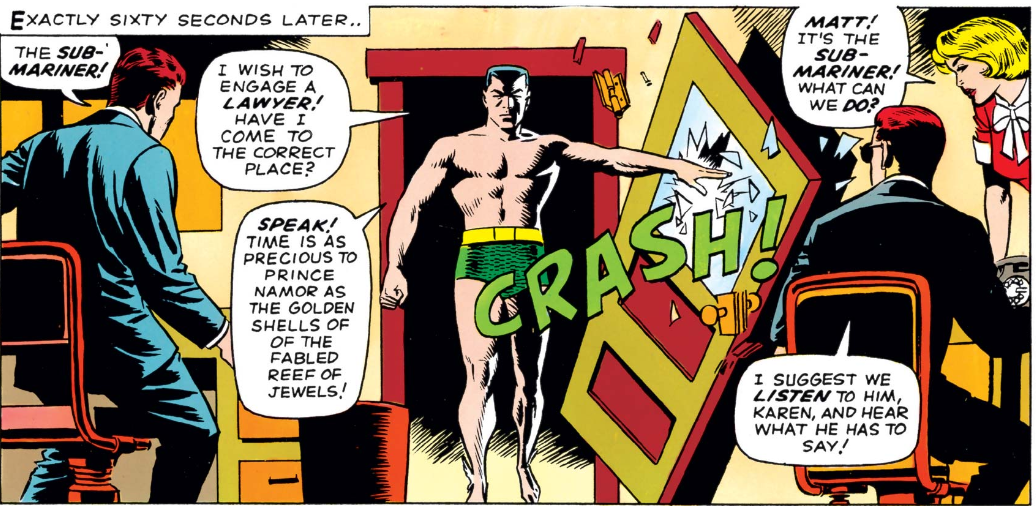

For twenty four issues, the first half of the first volume of Daredevil only focuses on three characters in any depth. Matt Murdock and Foggy Nelson are best friends and law partners, who start up the office of Nelson and Murdock. Karen Page is brought in immediately to act as their secretary. This small group and the overly dramatic connections between them, are the heart of the series.

Matthew Murdock

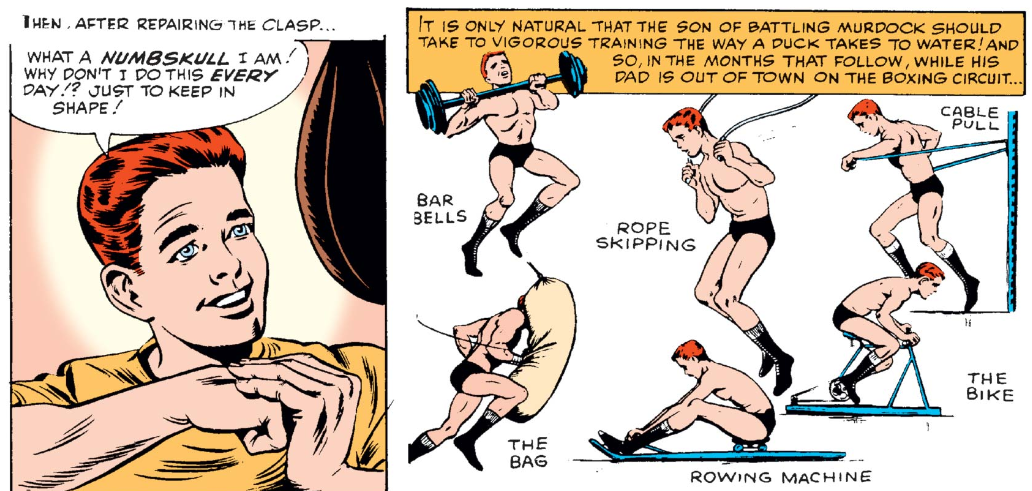

Matthew Murdock, The Man Without Fear, the titular Daredevil. Matt is a blind lawyer by day, and a crime fighting superhero by night. He has a superhuman radar sense that gives him increased perception abilities, and a vast array of related (and unrelated) powers. He received his blindness and radar sense from a truck spilling nuclear waste onto him as a child, while he was trying to save an old man. Also as a child, he was kept inside by his father relentlessly, in an attempt to keep Matt safe and successful in school. Matt’s physical prowess and fighting abilities are a combination of his radar sense and an intense training regiment he engaged in as a youth, in defiance of his father’s will.

Matt’s father, Jonathan ‘Battling Jack’ Murdock was a boxer, who knew the dangers and downsides of a life of fighting for survival. These drawbacks would eventually end Matt’s father’s life and inspire the creation of the Daredevil persona. “Battling” Jack Murdock was ordered to throw a fight by the mob boss known as The Fixer. He refuses to do so in part because his son was in attendance of the fight and he felt a need to set an example. Jack would be taken out in a hit organized by The Fixer for this, and subsequently Matt would create his alter ego. This all happens in the first issue, prior to the climactic finale.

While hunting down The Fixer, Daredevil gets the villain into a pursuit, on foot and barrel. In the excitement, the mob boss has a heart attack and dies, but reveals that it was his lackey, Slade, who actually pulled the trigger on Jack Murdock. Daredevil finishes the night by turning Slade over to the police, announcing his name as Daredevil and running off into the night, promising to return. It’s a bizarre and weirdly tragic story that in many ways would define Stan Lee’s run on the title.

In the well-known origin of Spider-Man, Peter Parker’s refusal to act against a criminal results in the heartbreaking death of his uncle. This instills in him the responsibility of using his powers when they can make a difference. For Matt the situation is a bit different, as he actively trains and equips himself with the goal of going against a specific person. He does so, and from his own view he is quite successful. There is little to no worry over the death of The Fixer, and Matt seems to be having more fun than anything else towards the end of his introduction. He does not labor over guilt from the death at his hands, instead he throws himself fully into the Daredevil alter ego, even when it is not convenient in his day to day life.

Taken at face value, after becoming Daredevil, Matt is a callous jerk who routinely acts in defiance of basic decision making. He is much more concerned with quips and flips than being effective. This of course is all in service of playing the part of bouncing, energetic superhero. In many ways this archetypal personality would be reflected years down the line in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, with the headliners of Iron Man, Doctor Strange, and Captain Marvel. The witty, headstrong protagonist is something the Marvel fan base will continue to gravitate to time and time again. There’s nothing all that unique about the characterization of Matt, as compared to other similar main characters that permeate the industry, especially at his origins. He becomes much more of a flawed individual, when viewed as a human who often hides his own intent and emotions. Sometimes from himself, intentionally or otherwise.

Matt experienced the terrible murder and loss of his father as well the traumatic accident of losing his sight early on in life. These events obviously deeply affect him, as he makes the decisions to train and reach physical peak, while running around doling out vigilante justice with billy clubs.This is clearly eccentric, but is also self sabotage, as his endeavors consistently jeopardize his day job of the ostensibly upstanding defense attorney. He is almost obsessed with his vigilantism, as he continually throws himself into mortal danger, risks his financial stability, and deceives those closest to him, all while gleefully offering neverending puns and sarcasm.

Accepting the main character’s behavior as erratic and manic makes the entire reading experience more enjoyable, and is encouraged by the plot. Future developments, such as the introduction of yet another alter ego for Matt Murdock further play into the idea that he is a bit more disconnected from reality than he realizes.

From the main presentation, it could be said Matt comes across as a boilerplate protagonist, a bit generic. This is subverted in a couple of notable ways, but foremost amongst them in terms of notoriety is the disability that spawns his superhuman abilities.

Despite it being his most famous characteristic, it can hardly be said that being blind is a focal point of the series in any way. Matt can’t see, but with his radar-sense it’s demonstrated that he has far greater and more precise perception than his sighted peers. This is the crux of his ability to be a superhero, but also could be seen to undermine his integrity a bit. Since he has the capabilities, he isn’t really needing the extra concern and care he is given from those around him. He is omitting parts of the truth.

Following that line of interpretation is shallow though, because the reality is those with disabilities are indeed capable, they just face individual obstacles that severely impede them. Matt does not go into depth on the real day to day hardships he faces, despite his radar-sense, but then he is not exactly the most self-aware at all. Matt as a character, much like the entire series, comes across more fleshed out when taking into account the struggles he, as a fictional personality, would omit when retelling. The small moral conundrums and stark dichotomies in Matt’s life come together to create someone who, at the very least, is an excellent vehicle for melodrama.

Foggy Nelson

The other half of the law office, Franklin ‘Foggy’ Nelson is Matt’s best friend as well as coworker. He is petty, jealous, and overall a bit immature. He constantly feels inadequate, comparing himself to Matt despite the fact they are of very similar means. Add on top his pining over their secretary Karen Page, who is more interested in both Matt Murdock and Daredevil each, and Foggy can come across as an unlikeable guy. Irrational at times, and frequently self-serving, the quirks of his character thankfully come across as lighthearted thanks to the light hearted tone of the series. The problematic nature of much of Foggy’s behavior is rendered at least comical and at most justified in relation to the context of many of the convoluted situations. Foggy deceiving his friend’s by pretending to be Daredevil is forgivable and funny when juxtaposed to the fact that Matt does the opposite on a daily basis.

Appearing slightly shorter and more portly than his superhero friend, Foggy’s realistic character design is a welcome rarity on the comics scene. Unfortunately this serves for a few cheap gags, but does differentiate Foggy from his superhero friend, and the usual muscle bound foes Daredevil goes up against. The limited cast in the series almost forces the story to push and pull the main characters around their respective moral spectrums, and being more reflective of the everyman works in Foggy’s favor.

The heart of the relationship between Matt and Foggy is complicated at times, but sort of redeems them both. His best friend is not just keeping him in the dark in an attempt to keep him safe, along the lines of Superman or Spider-Man. Instead Foggy’s bff is actively lying about his disability, and frequently using his powers irresponsibly or inappropriately. Daredevil consistently leads villains to the law office, and occasionally uses his super hearing to listen in on his colleagues private conversations, and then subsequently deceive them. While this spin is not the focus of the series, it does help to shine a redeeming light on a character some might find a bit off putting or bland at times.

Karen Page

The third member of the law office is secretary Karen Page. Coming across as relatively likable and normal, her backstory is certainly the least explored of the main cast. She is the typical comic book stereotype of a 1960’s woman, written by a man. At times immature and boy crazy, Karen can come across as juvenile frequently, despite her not being notably young or anything of the sort. In the contemporary X-Men series, Lee sometimes gets away with awkwardly misogynistic depictions of the singular woman character, Jean Grey, by specifying she is younger and less experienced than her teammates. Besides potentially an education in law gap, there is no real scapegoat in place for Karen.

Karen is immediately smitten with Matt Murdock, but laments the perceived inherent truth that a blind man could never marry a woman who can see. It’s a weird thought process that both Karen and Matt have, just patently refusing the idea of a blind person finding love. Along with her crush on Matt, she falls for both Foggy, Daredevil, and the idea that Foggy could be Daredevil.

Some of Karen’s thoughts and dialogues are seemingly results of a man trying to replicate those he has seen from others, but does not quite understand. A more practical depiction would likely touch on the power imbalance of both her bosses having romantic interest in her as soon as she is hired. Of course this is a superhero comic book from the 1960’s, and as mentioned previously there are only three main characters, so they each have to stretch and fill narrative slots. The constrictions of the format pad out the lesser writing job done for Karen, much like it softens the blow from some of the other two’s more outright malicious or nonsensical actions.

At the end of the first twenty four issues, Karen has a lot of tropes and associated baggage placed on her that has to be overlooked, but if that is possible, she has a few shining moments. She comes out a bit inconsistent and not always likable, but compared to many comic side characters and romantic interests particularly, Karen Page has a burgeoning personality and seems poised for positive character growth.

Year One

Daredevil comes right out of the gate stumbling. The first issue is drawn by Bill Everett, and while it is well done, it’s the only one he ends up completing. After the debut, Joe Orlando picks up the next three without too jarring of a change, but the first four issues as a whole leave a bit to be desired artistically. While completely inoffensive and passable, the art’s largest drawback is that it is seemingly trying to replicate Kirby and to an extent Ditko, to varying levels of success. Both Everett and Orlando’s Daredevil can look like a posed mannequin instead of an acrobat in motion more often than not.

The stilted depiction is accentuated by the signature flowery dialogue of Lee. There is a definite sense of trying to cram the product with content in the opening few issues. The scenes are rapid and all over the place, but filled with tons of text to stretch the reading time and each scene out longer. While fighting Electro, Daredevil manages to fly a spaceship into space and back down to Earth in the span of a couple of pages. These types of hijinks are the heart of this era of Daredevil. The tone is the epitome of classic costumed vigilantes and that has to be accepted and enjoyed for the series to have a positive impact in any way.

Bolstering the borderline corny setup is the monster of the week structure taken by the comics. While not uncommon to comics at the time, it is notable that storylines barely stretch over multiple issues, and the villain is usually unique for each of the first ten or so issues. This adds to the memorability of the villains since they get books entirely dedicated to both their origin and fight with Daredevil. However it can suppress interest in the established cast of the book, as they don’t make many lasting or impactful decisions during this stint. The small bits of lasting continuity tend to happen in crowded word balloons over a single page of conversation between Matt, Foggy, and/or Karen bookending the issue.

The plots can be overly melodramatic, but also compelling, such as when Karen insists Matt get an experimental surgery to cure his blindness. However since he is scared it could turn off his Daredevil powers he does not want to go through with it. The biggest drawback to these dilemmas specifically is that the crux of the problem tends to just be that Matt can’t date Karen because he is blind. The inherent idea from both of them that a relationship is out of the question is so manufactured for the plot it feels barely plausible. To be fair though,The world of Daredevil, and Marvel comics in general, does not necessarily thrive in the plausible.

One of the more notable aspects of the first half-dozen issues is Daredevil’s costume. He is sporting a garish yellow and black color scheme as opposed to his usual muted shades of red. The original suit is passable, and gets points for more resembling an acrobat costume, which is the inspiration. However as soon as the new crimson costume appears on the page, it feels more natural for The Man Without Fear. Along with the red apparel comes creator Wally Wood, who puts in a distinctly personal run on the title.

Still being the 60’s, there is no escaping the attempts to build off Kirby’s influential artistic style, but Wally Wood is the first on this series to make the style his own. Daredevil begins to move through the space a bit more like Spider-Man, making the dynamic motions appear more believable and natural on page. The ‘Marvel method’ of making comics (art done first, dialogue inserted second) clearly comes through with Wood, more so than the previous Orlando. Arguably there is a wide array of pages that are more understandable when simply parsing the art, and ignoring the dialogue altogether. Lee’s signature verbosity can just over explain exactly what has been drawn, and frequently slows the book to a crawl. Given the weight of the story which is held up by the art, it’s only slightly surprising to come across the tenth issue of Daredevil. Unlike the rest of the first fifty, this issue is not written by Stan Lee, but instead Wally Wood.

The tenth issue is a bit of a breath of fresh air, being distinct in style from the surrounding bunch. While clearly intentionally keeping with Lee’s signature tone, the plot of the issue is more complex to start. The story involves a group of villains, The Ani-Men, who should feel generic with names like Frog-Man and Ape-Man, but they each have a lot of charm. There is a more clear arc, and the writing feels more purposeful than the previous stories, which were more concerned with explaining the page rather than advancing the plot. There is a case to be made that the issue benefits from the singular writer/artist, as opposed to the usual tag team approach. The entire story is a setup to a mystery that will be concluded in the next one, while claiming that all the hints the readers need are there if they can find it. Even a small gimmick like that feels innovative given the context.

This is not to try and elevate the comic too much and say that it is some masterpiece, or even to say it is not clearly replicating Lee. However it shows, at the time especially, that Lee is not the only person who can effectively write his characters. It proves in some cases a fresh perspective brings new life to a series. By the next issue though it is clear these are not the takeaways, at least from those behind the scenes.

The eleventh issue, and all those that follow up to number fifty are given back to Stan Lee’s pen. Wally Wood departs from the book, and the second half of his story is given to Lee to wrap up, cliffhanger and all. In an awkward move, Lee decides to print in the comic a message to the readers about the situation. He proclaims that Wood left it to Lee to finish the story without giving him the ending or any notes. He was clearly both covering in case the story came out subpar, but was also publicly shaming Wood. The wrap-up is fine, and honestly would have been more enjoyable if it was not undercut by the meta commentary informing of its potential flaws.

At this point in the narrative, Matt decides to give Murdock and Nelson the same treatment Wood gave Marvel, and he gets out of there. Bob Powell does pencils with Wood, and does a few issues on his own in the aftermath of the departure.

John Romita Sr, comes in after Powell and brings a striking look to the book. Under Romita’s pen the comic gets darker, and more detailed in a borderline striking departure from form. This won’t last too long, but is another welcome shake up to the already formulaic series. The evolution and maturity of the stories does ramp up with the new art, and the second year of Daredevil ushers in a new rhythm for the title.

Year Two

Arriving at issue twelve of Daredevil, the Marvel Universe as a whole is picking up in quality and it’s noticeable. While Wood’s art was fantastic, the book just did not really ever take off on his run, possibly due to the creative challenges behind the scenes. For Romita and Lee, the chemistry seems to be there from the start, and the mindset on how to present the stories has changed up. Multi-issue arcs become quite common, and some light plot throughlines begin persisting and progressing instead of snapping back to a hard set status quo after each caper.

While the first year of comics had a tendency towards introducing and defeating villains in a single issue, the second year sees a lot more recurring antagonists. The building of storylines and slowly growing complexity of the series is starting, and welcomed. Prior, the narrative felt like it was spinning its wheels trying to establish a consistent status quo. In the second year, there is more of an emphasis on character development. Daredevil also starts to come up against obstacles that are simply too large for one man, fearful or not.

With his reputation growing, the story sees Daredevil develop into a more understood threat by those around him. His enemies, such as the Masked Marauder and the Owl, begin employing muscle to try and head off Daredevil instead of opting to face him themselves. While inspiring fear may bring him some level of respect and acknowledgment, it also highlights the sheer ineffectiveness and overall futile effort of Matt Murdock to deal with crime.

As one man, no matter how good he can punch and kick, he is unable to physically take down multi level crime organizations that are embedded into their communities. Arguably, Matt could have better luck utilizing his law degree to elicit local change, rather than punching people. This dichotomy of breaking and enforcing the law in order to better society is recurring and compelling, but rarely explored in depth.

Closing Arguments

The first two years of Daredevil’s existence are the epitome of a beginning comic book superhero. Tropes and plot contrivances are abundant, the tone swings from lighthearted to surprisingly dark, with Stan Lee’s wise cracking dialogue shepherding the story along. Compared to modern books, there is not too much from this classic that hasn’t been seen before. However with services like Marvel Unlimited, the series becomes as accessible as any app, and Daredevil comics become a fun and easy way to waste time instead of the horrors of social media.

For the most part, the audience for this in the current day is mostly folks capitalizing on nostalgia or interested in the history and development of Daredevil. Arguably there is a lot of fun to be had, the book just requires a certain approach and limited expectations. The reader who idolizes their hero, and wants a paragon of virtue or a stone cold badass, will be disappointed. However the reader who is ready for melodramatic plots, severely flawed characters, and is willing to skip some text in the neverending fights, will have a solid experience.