The First (And Best) X-Men Reboot

Merry Mutant Review

The Wein and Cockrum (and Claremont) Run

The year was 1975 and the Uncanny X-Men had been captured by low sales (and a certain mutant island that walks like a man). The former two years of publication had seen the X-Men title in reprints, and honestly, the book had never been much more than a mid-tier offering from the Marvel line. There seemed to be little clamor for a return of the children of the atom, but their memory, and potential commercial viability, had not been lost completely.

In a position similar to the start of Kirby and Lee’s X-Men, Marvel comic sales were up, and the company was looking to expand. Instead of launching a new title the decision was made to reinvigorate the mutant team with a new, international lineup.

Len Wein and Dave Cockrum are tapped to spearhead the reboot with Giant-Size X-Men, an extra large issue that introduces each of the new team members. Chris Claremont picks up on scripts with X-Men 94 immediately after the initial story. Claremont would go on to develop the already compelling cast, and pen one of the longest and often lauded runs of superhero comics.

Storm, Nightcrawler, Colossus, Banshee, Thunderbird, Sunfire, and some guy called Wolverine. In rapid succession, Giant Size introduces mainstay after mainstay to the X-Men universe. While the creators could not have foreseen their longevity, there is a remarkable amount of characterization planted here that will be reflected throughout the years for these new heroes. This installment of the Merry Mutant Review goes through the birth of the All-New, All-Different X-Men in Giant Size X-Men and (Uncanny) X-Men 94-96.

Help, I’ve Lost My Strange Teens! (Giant-Size X-Men)

Professor Charles Xavier has lost his team of young superheroes to a living island, and it’s up to you to get them back. For all intents and purposes, this is the premise of Giant Size X-Men, and it works remarkably well. By focusing on expanding the team’s roster the book simultaneously widens the overall Marvel mutant world, and establishes an intimate, character-focused storytelling style.

Giant Size X-Men opens with Professor X touring the globe to recruit a new band of mutants. After gathering them, he sends the team off to a mysterious island, where the former X-Men team was last seen before mysteriously disappearing. The plot itself is relatively simple, with the majority of time and care being placed upon the new characters. There is a surprising amount of characterization that will persist with new team members, especially considering Len Wein is writing, as opposed to Chris Claremont who is often credited with the development of the Giant Size team due to his extended time with the title.

The first pickup is the fuzzy blue elf, Kurt Wagner aka Nightcrawler. The teleporting mutant is being chased down by a mob armed with torches and pitchforks when Professor X arrives. As with most of the new members, there is a small interaction between Xavier and Kurt, before the latter is convinced to join up and help find the lost team. This pattern of recruitment continues for the rest of the team, with a specific weight being placed on their nationalities.

Out of the new designs, Nightcrawler’s is one of the most striking, with his bubbly, fun personality reflected through his unique aesthetic, in an almost inverse fashion. A sincerely charming devil. He does not play a massive role in the overall story, but his appearance and its implication create a sense of intrigue. Mutants who cannot pass as humans in any way are an idea that has not been explored by the series in any real depth at this point in publication history, and the existence of such mutants establishes a new dynamic in the broader conversation. For the broader population, if any number of mutations begin to express themselves in ways that are incapable of being concealed, then the struggles of the mutants begin to more closely resemble real-world communities in borderline meaningful ways.

Up next is Wolverine, and the short, stout enigma of a Canadian is pure and untainted by the baggage that will weigh him down in the decades to come. He is gruff and mysterious and has claws that may or may not be a part of his gloves. There is a base for the character that is clear and captivating, and it is hard not to enjoy him. While remaining capable and dangerous, this version of Wolvie is more goofy than cool, in the best way possible. Still, his characteristic direct refutation of established authority and his willingness to capitulate morals for the greater good are seeded in Giant-Size and the preceding Uncanny issues.

Sean Cassidy, Banshee, is recruited in just a couple of panels. The Irish mutant is not new to the mutant world of Marvel comics and continues to work as a side player. His past as an Interpol agent and police officer provides a unique perspective, as does his age. Those aspects help Banshee work as an understandable archetype, though they do not necessarily inspire curiosity for the character.

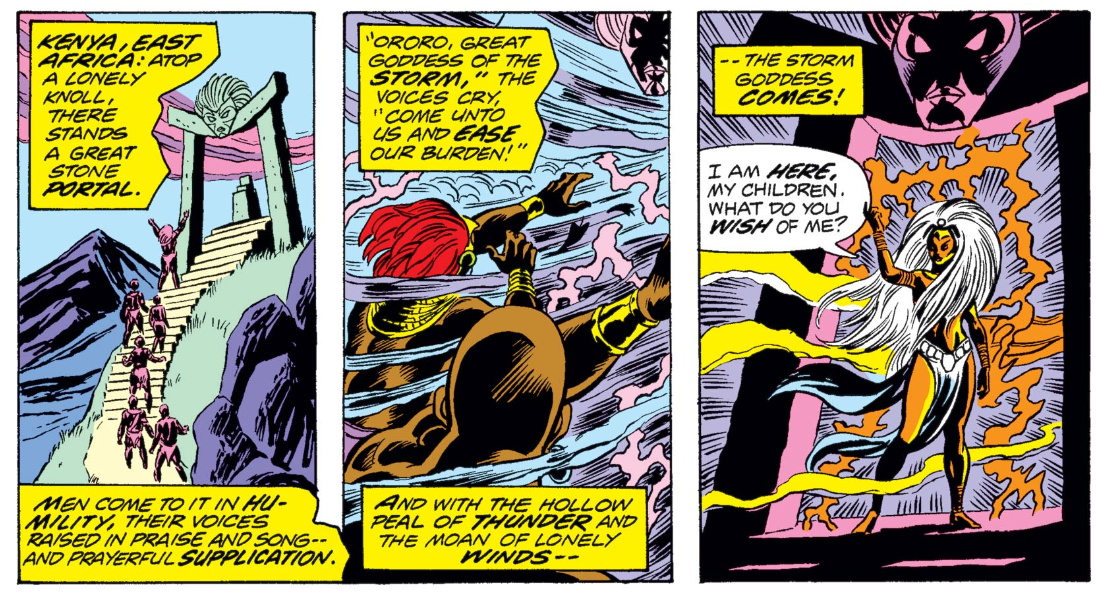

Perhaps the most important new mutant is the next to be brought into the fold, Storm. Ororo Monroe’s opening sequence is vital to her arc as a character and presents some of the most compelling struggles that will persist down the X-Men line. At the outset of Giant Size, via her mutation that gives her control of the weather, Storm presides over Kenya. She reinvigorates areas of dying land and presents herself as a goddess of protection.

Ororo is quite plainly demonstrating the highest form of Xavier’s own dream. She is living in unity with the humans of Kenya and asks for nothing in exchange for her services. Xavier insists that she is not a god and that she has a responsibility to her people, and to the world of mutants. He is wrong, and frankly, projecting. Did Storm risk the lives of a young team in pursuit of her own goals? Is she not protecting the Kenyan mutants alongside their human counterparts? Such a read may be a bit more in-depth than the text is expecting, but it is required to fully contextualize the character of Storm that will emerge down the road.

Reintroduced and quickly recruited out of retirement, Shiro Yoshida is the Japanese mutant hero Sunfire. Xavier mentions Shiro’s distaste for the Western world, drawing a parallel that walks the line of inviting more serious themes. This is bolstered later on by an awkward change of mind about being on the team. Sunfire decides to quit, but in just a few panels has inexplicably changed his mind, with somewhat of an insinuation of more sinister persuasion from Xavier.

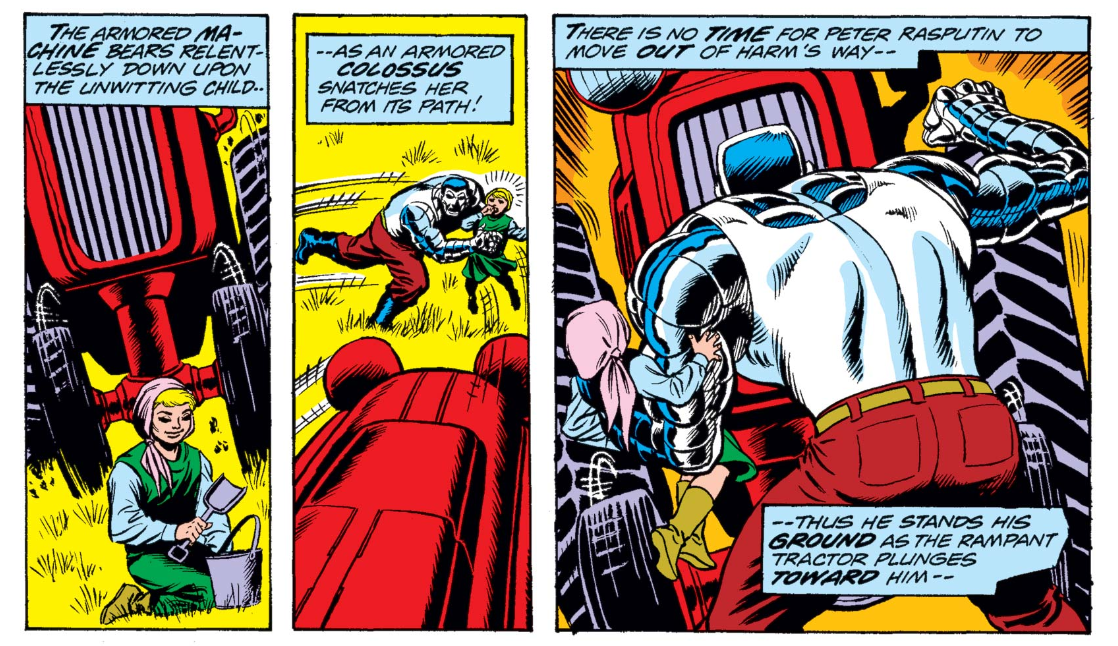

Piotr Rasputin and John Proudstar are Colossus and Thunderbird respectively. The first is a stoic Siberian who can turn to steel, and the second is a hot-headed Apache with superhuman strength and speed. They are both confronted with the same offer from Xavier, one that calls them to abandon their struggling people in response to a greater calling. Both will be plagued by the incompatibility of Xavier’s dream and actions with the suffering they left behind for the rest of their lives.

The remainder of the issue comes together to deliver a classic, competent superhero adventure. Interactions between the characters are charming, with each new member getting small moments to shine. Later established truths, such as Storm as a leader and Wolverine as a little freak start to take root within the initial mission. With some teamwork and power combos, the international X-Men are able to rescue the prior team from the grips of Krakoa, the living island.

The Leader of the X-Men (Uncanny 94-96)

After Giant Size, three major events occur over the three subsequent Uncanny X-Men issues. The departure of the original team, the death of Thunderbird, and of course the slaying of Kierrok the Shatterer of Souls, the demon who lives out back of the mansion. Surprisingly, the connection between these events is everyone’s favorite fail-son, Scott Summers.

Cyclops is arguably the protagonist of these issues, operating as a reader surrogate for both new and former fans. The classic team deciding to part ways with the newer X-Men creates a perfect situation to explore Scott. His turmoil at being separated from his former teammates is intriguing and potentially cathartic for fans of the older comics, while the new cast keeps past stories and lore from taking precedence.

Uncanny 94 opens with all of the original X-Men besides Scott leaving to lead their own individual lives. His inability to control his optic blasts is the main given reason that Cyclops feels trapped. The risk of an accident weighs too heavily on him to leave the Xavier Institute permanently. It is noteworthy that control of mutation does not ever seem to be even a possibility for Scott, despite that being the entire premise of the school. His childhood accident is often blamed, but whatever the reason, the flaw adds some spice to an often bland character.

Following the exodus of the established members, Cyclops wastes no time trying to whip the new team into fighting shape. There is a clear incongruity between the new X-Men and the style of learning and leadership that Xavier and Cyclops utilized with the former team. There is irony in watching Scott lean on the tried and true tactics of straightforward rules and organization, despite the clear and constant indications that they are not fit for his current situation.

When the all new X-Men set out on their first real mission to stop Count Nefaria and the Ani-Men from instigating a nuclear apocalypse, they were understandably unprepared. Since it is a Marvel superhero comic book, there is an impression that the team will overcome its shortcomings and unite to save the day. In some ways, this comes to pass, but the fate of Thunderbird underscores the new direction the line is adopting.

The harrowing mission sees Scott stumble to work with John, and from the perspective of the fearless leader, he makes two blunders that place his teammates' deaths squarely on his shoulders. He decides to leave the unconscious Banshee and Thunderbird behind, and then subsequently wastes the rest of the team's short time to return and help the abandoned X-Men, opting to instead try and shut down an already out-of-commission missile launch computer. The separation and delay set the stage for Thunderbird’s tragedy. It’s not clear if any of the others feel strongly about Scott’s actions but he certainly .

Opposite from Cyclops there is Storm. She is not given the same front-and-center attention necessarily, but she is rapidly evolving into her familiar character. While Scott is barking orders and making mistakes, Ororo is establishing a bond with her peers, and already routinely solving major issues on the battlefield. Her competence becomes clearer, as Scott’s grows more questionable and entrenched in a losing ideology.

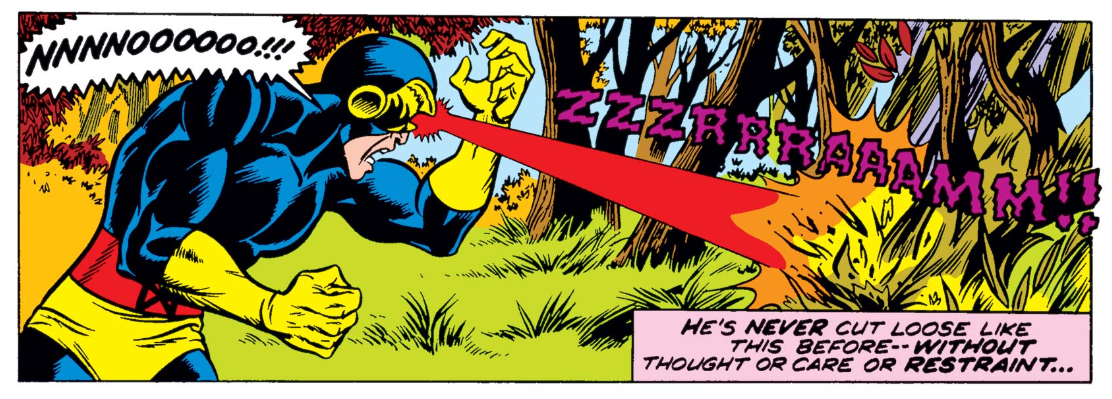

Once the X-Men return home from their fateful encounter, the compounding guilt and trauma from recent events proves too much for Cyclops. He lets the mounting frustration get to him, and he unleashes an angry and uncontrolled blast, which devastates an area of land on the Xavier estate. A reminder that all actions have consequences comes quickly and swiftly.

There happened to be a mystical cairn housing a demon in the way of Scott’s destruction. He releases Kierrok onto the grounds, and at the same time, the rest of the team is enjoying a tea party in the mansion. Hijinks ensue.

In fighting the demon Wolverine engages in a manic fury that is more extreme than seen before but will become his staple berserker rage. Notably, it is painted as a parallel to the outburst from Cyclops, while Wolverine revels in his expression of power, Scott laments his own. The connection between the two men is a long-running element worth watching, and the lack of Jean Grey creates a unique context for them.

The finale of the issue is a riveting sequence of Storm, once again, saving everyone. The pattern of her success and contrast with the assumed leadership is hard to disregard.

Cockrum and Claremont

The dialogue and interactions between the characters are already selling points for this book, especially compared to its contemporaries. While Claremont may just be getting started, the unique voices and sprawling cast are already showing to be a positive for the series, while they would be a challenge under the pen of certain creators. His tendency to be verbose and give lots of time to side characters is present in these issues and isn’t going anywhere.

The writing is to be applauded throughout these stories, but if any single element of Giant Size or the subsequent issues elevates them on a moment-to-moment basis, it is the art from Dave Cockrum and company. New and old, each of the costume designs are distinct and eye-catching. Personality and tone are intentionally emanating from panel after panel. In complete contrast to each other, the physical comedy of Thunderbird being ejected from the Danger Room works just as well as a dramatic issue-ending thunderstorm from Ororo. The story and art work seamlessly together.

There may be some fingers pointed at a face or two from Cockrum, with a few panels ironically approaching the uncanny valley. Generally, though the faces are distinct and do a very effective job of displaying attitude. Everything is sharp and vibrant, and the more awkward panels are usually the result of Cockrum trying to capture different angles and perspectives for each of the many characters on the page. Combining a strong grip on expression and tone with careful coloring, the art for this run comes out of the gates as strong as the writing.

Citation Station

- Giant Size X-Men, Len Wein (writer, editor), Dave Cockrum (penciler, inker), Peter Iro (inker), Glynis Wein (colorist), John Costanza (letterer).

- X-Men 94, Len Wein (writer, editor), Chris Claremont (writer), Dave Cockrum (penciler), Bob McLeod (inker), Phil Rachelson (colorist), Tom Orzechowski (letterer).

- X-Men 95, Len Wein (writer), Chris Claremont (writer), Dave Cockrum (penciler), Sam Grainger (inker), Petra Goldberg (colorist), Karen Mantlo (letterer), Marv Wolfman (editor).

- X-Men 96, Chris Claremont (writer), Bill Mantlo (writer), Dave Cockrum (penciler), Sam Grainger (inker), Phil Rachelson (colorist), Dave Hunt (letterer), Marv Wolfman (editor).