WAR, What Is It Good For?

Politics

At the beginning of the year, Split Ticket, a site dedicated to political data analysis, released its Wins Above Replacement (WAR) models for the 2024 US elections. Self-described as a candidate quality assessment, the goal of the score is to identify the politicians who perform at a higher level in elections when compared to a generic alternative. The site states their models “assemble a ‘fundamentals’ based outcome estimate for a race by controlling for seat partisanship, incumbency, demographics, and money and help us project how a race ‘should’ have gone…”

A statistic of this sort certainly has uses, as it could provide context and insight into voting behavior. Of course, there are limitations to what can be learned by comparing actual data to a generic projection, as voters' choices are always actually between two distinct individuals. While the WAR score may accurately reflect the candidates who overperformed in a specific election, misguided attempts to replicate successful strategies without considering context are bound to lose.

To Be Rather Than To Seem

Amid the 2024 presidential election cycle, Kamala Harris was thrust into the spotlight of American politics, and right alongside her was the state of North Carolina. While both Harris and NC were always going to be influential players in the election, the Democratic Party’s swap from Biden to Harris flipped the conversation on its head. Almost immediately, a narrative emerged that Harris was much more likely to win with an electoral path through NC than was predicted for Biden. The polls reflected the shifts in sentiment initially, but Trump maintained his consistent slight edge and even pulled away as election day approached, which was often disregarded as insufficient polling by those betting on the Democrats.

For someone familiar with the state, these assessments of NC likely cause a pause, as it is disconnected from the current general sentiment, and would be a historic win if true. The state has not swung for Democrats in a presidential election since 2008 and before that, 1976. Even when Obama won, he finished with a slim 49.7% of the vote against McCain’s 49.38%, a difference of just over 14,000 votes out of a total of 4.3 million. Over the years, numerous statewide elections, notably that of the gubernatorial, have proven a North Carolinian willingness to separate the top of the ticket from the bottom. Despite this, in the 2024 arena, enthusiasm markedly increased across the board with Biden’s exit and Harris’ entry, and NC was one of the select swing states that received an increased scrutiny and discourse around flipping blue due to the Democrat shake up.

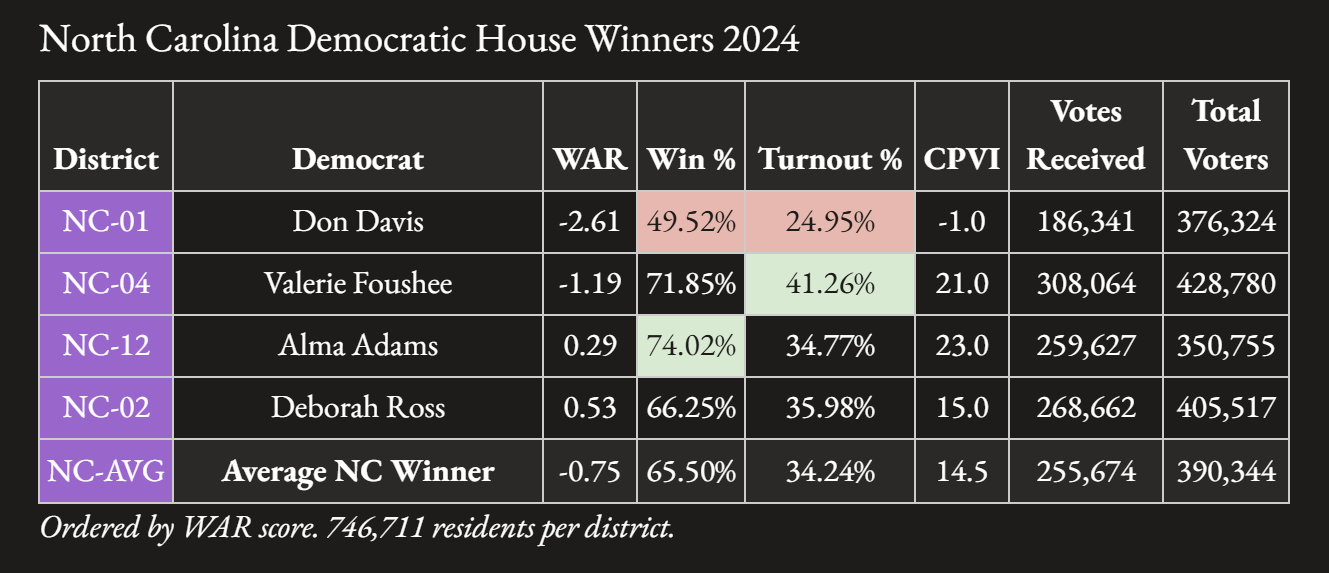

Despite my belief that the national outcome was ultimately a coin flip, the NC path for Harris was never as likely of a proposition in my eyes. The optimism in the prediction seemed rooted in a wish to deflect from the Democrat's declining poll position in the midwest and frankly displayed a detachment of how thoroughly the GOP holds NC politics captured. Between gerrymandering and voter suppression laws just to start, the state was never in a prime position to make a bold swing. When I noticed the WAR score promoted NC-01’s Don Davis as a model of success for the party, it prompted the pause of the same sort from me as the idea that Harris would win the state simply by replacing Biden in name.

Harris’ small polling surge and eventual slight defeat in North Carolina are results of a similar limited perspective that is holding back the people of the party and underpinning the strength of a score like Davis’. Using the WAR value in conjunction with data from Ballotpedia, such as voter turnout and election win percentage, there is evidence that the Democrat's highest quality House candidates from 2024 largely represent unpopular, declining ideas and a losing strategy going forward.

Establishment Coalitions

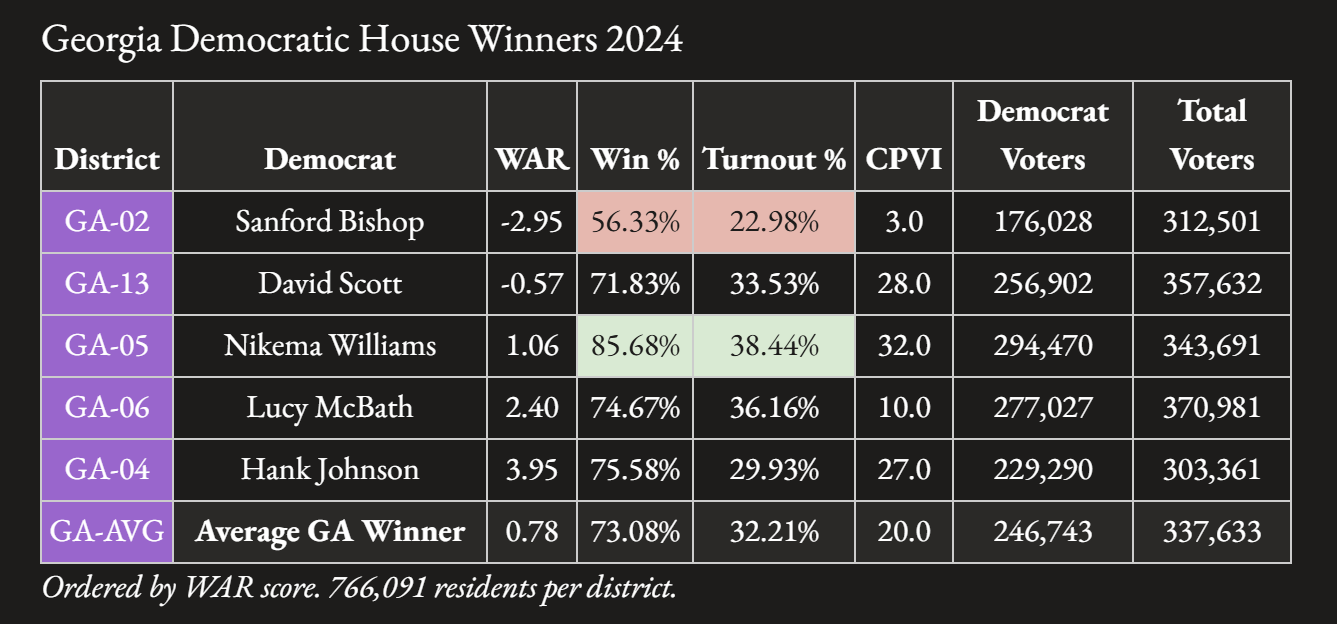

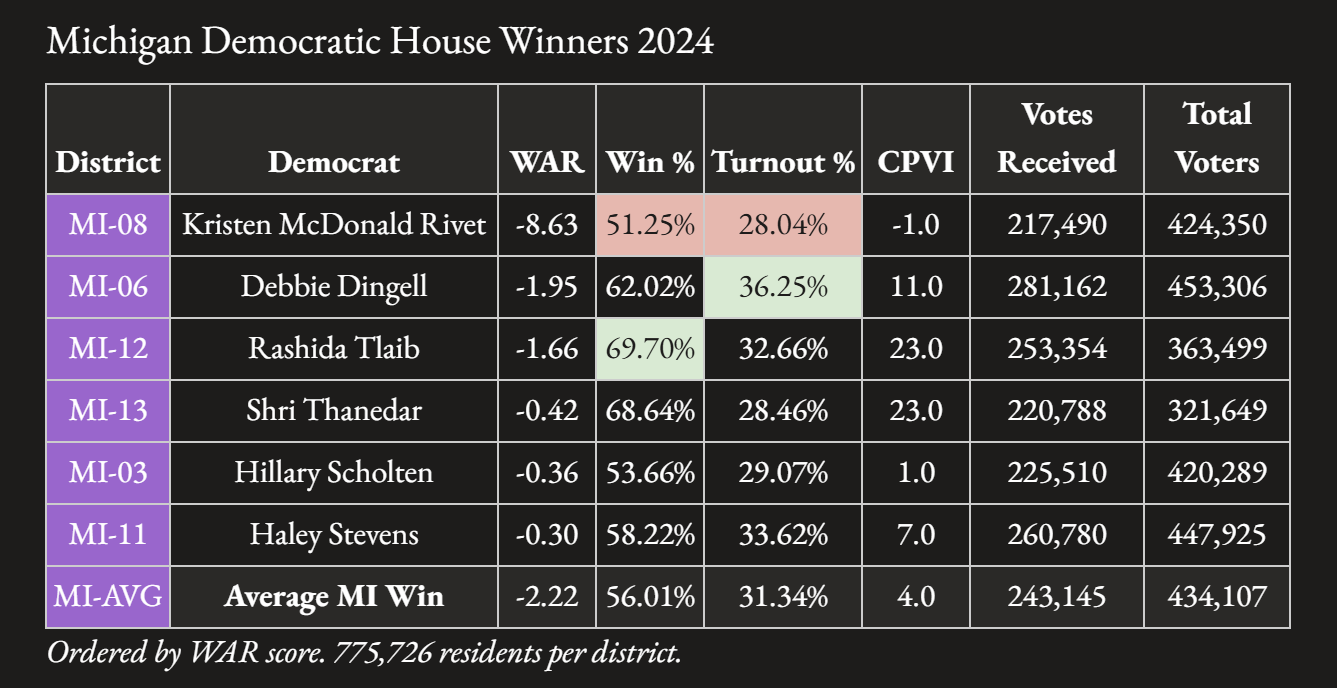

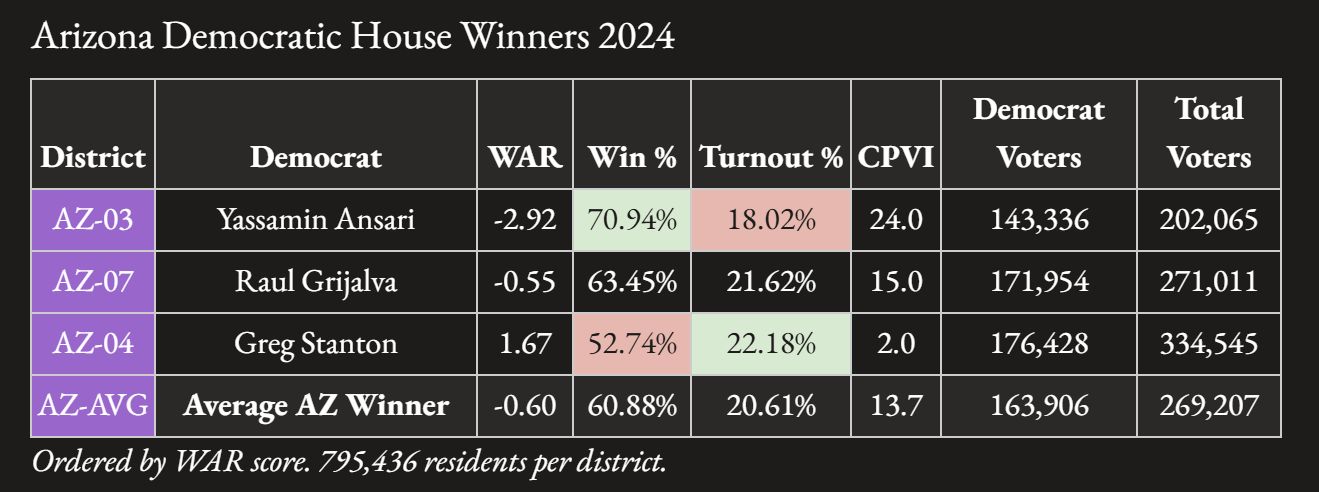

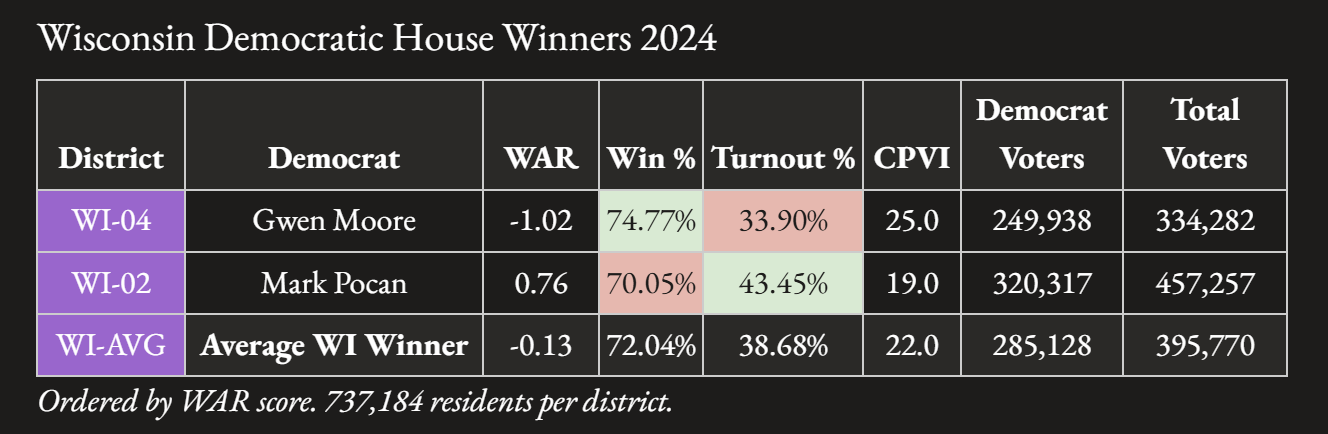

The swing states can be evenly split into two groups where the candidates with the best WAR score share various characteristics. For the first collection of states, the top WAR candidate also ran in the district with the lowest Cook Political Value Index (CPVI) score respective to the winning Democratic districts in their state. Additionally, they were the winning Democratic candidates with the lowest turnout and win percentages. For these states, the “highest quality” candidates were those that received the least votes and ran in the tightest districts.

The top WAR scorers in these states formed anti-Trump coalitions in line with the attempts made by the Harris campaign on the national stage. These candidates did not win with a wave of nonvoters entering the democracy, nor did they have a unique, inspiring effect on their base. They snatched victory from the jaws of defeat through a combination of pandering to the establishment, centrist Republicans, and luck in the form of the average Trump voter’s disloyalty to the bottom of the ticket.

The candidates in this group benefited from the campaign that Harris ran on, with her appeal to centrist, high propensity voters being most impactful in the low turnout, swing districts. However, it is difficult to see a viable extension of their coalitions unless the party entirely becomes untethered from coherent ideology.

NC-01 is one of the most instructive districts in the country for comprehending the limitations of the establishment coalition. Though the district has been held by the Democratic party since 1900, recent partisan state gerrymandering has made it the state’s most competitive. Democrat Incumbent Don Davis held NC-01 with a plurality, and he had the Libertarian candidate, Tom Bailey, and his 2.6% to thank in part.

If the Libertarian Party had not run a candidate in the district, Davis would have likely lost but still would have outperformed Harris. By most standards, the folks voting for the Libertarians in NC are not far left, progressive, or even moderate. They are, by and large, right-leaning individuals who are disillusioned with the Republican Party as an organization. This assertion is supported by Trump winning the district by three points.

The Democrats are hitting the cap of the centrist establishment coalition in NC-01. Davis' strategy succeeded, but when the third party is absent and/or Trump is out of the picture, it falls apart. Further capitulation to the right will suppress voters on the left and will not motivate nonvoters. Elections come down to slim margins when broken down into voters who actually shift from year to year, and sometimes, the tight race allows the establishment coalition to come out on top in districts with low turnout. However, counting on these small odds based on centrist swing voters becomes more questionable as election participation inevitably increases.

The Harris campaign in NC is a clear example of how Democrats will struggle to win if they suppress their voters in order to motivate a select group of historically high propensity centrists. Harris saw her popularity peak when she first entered the race, as there was a groundswell of support from the base, but she steadily lost her coalition as she ran to the right and repeatedly affirmed herself as an establishment candidate. She may have picked up a Cheney or two, but she lost the election on the way. Perhaps if RFK had stayed on the ballot then Harris could have pulled out a plurality, though it didn’t work out for Clinton in ‘92 in the state, and she seemed to be targeting the same constituency. Still, the tactics employed in NC-01 and the Harris campaign can be seen grabbing tight victories in the swing districts of GA-02 and MI-08.

The top candidates from Michigan and Georgia share the pattern of close, low turnout elections. Sanford Bishop arguably plays the strategy the best, winning a higher percentage than his MI or NC counterparts. His instance implies the strategy thrived with lower turnout and fewer options, as Bishop turned out fewer voters than Rivet or Davis, and did not have to contend with third parties.

Presuming voter participation increases over time, GA-02 will find itself in a similar situation to MI-08 and NC-01. Gains from embracing the establishment right will soon erode the support for Democrats to a precarious plurality as anti-establishment sentiments dominate American voters across the spectrum. The strategy of prioritizing centrist Republicans risks alienating the left and even the more populist-minded nonvoters. When Democrats align with the status quo instead of change, their candidates find themselves boxed into coalitions that are almost as small as possible by definition, despite having deep pockets.

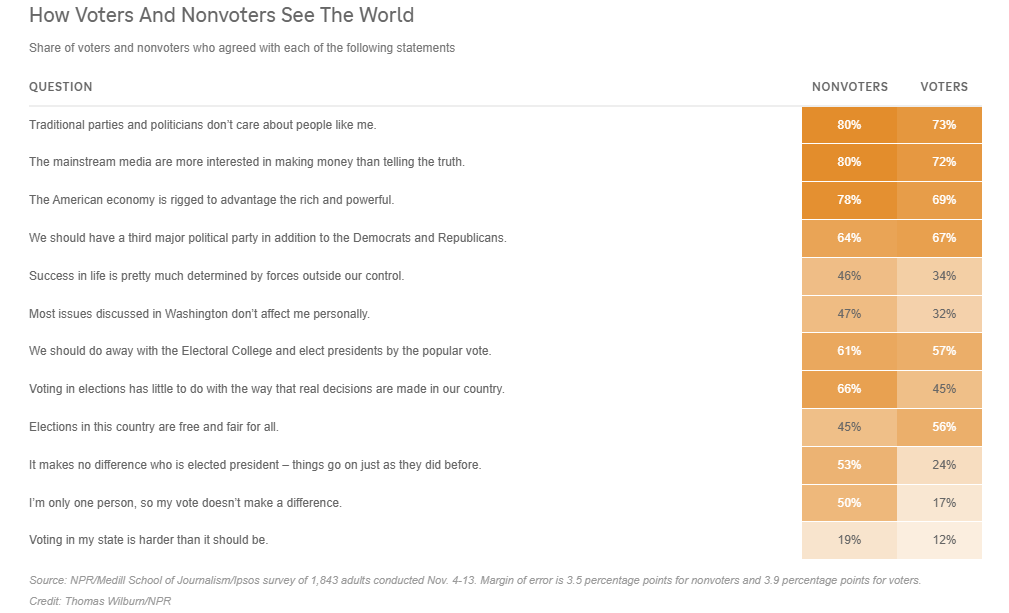

Picking up voters from the high propensity center right, in many ways, is the easy option, as they are more likely to vote and to be turned off by an abnormal top of the ticket. However, it becomes unsustainable if the Democratic party embraces the establishment right in a country of rampant nonpartisan anti-establishment stances. Appealing to the nonvoter is a more sustainable strategy for a politician who plans to deliver actual results in a political environment that consistently values change. A failure to appeal to the nonvoter is shared across both groups of top WAR candidates, though it manifests in the other half of states among districts of drastically different partisan makeups compared to the competitive districts in the first group.

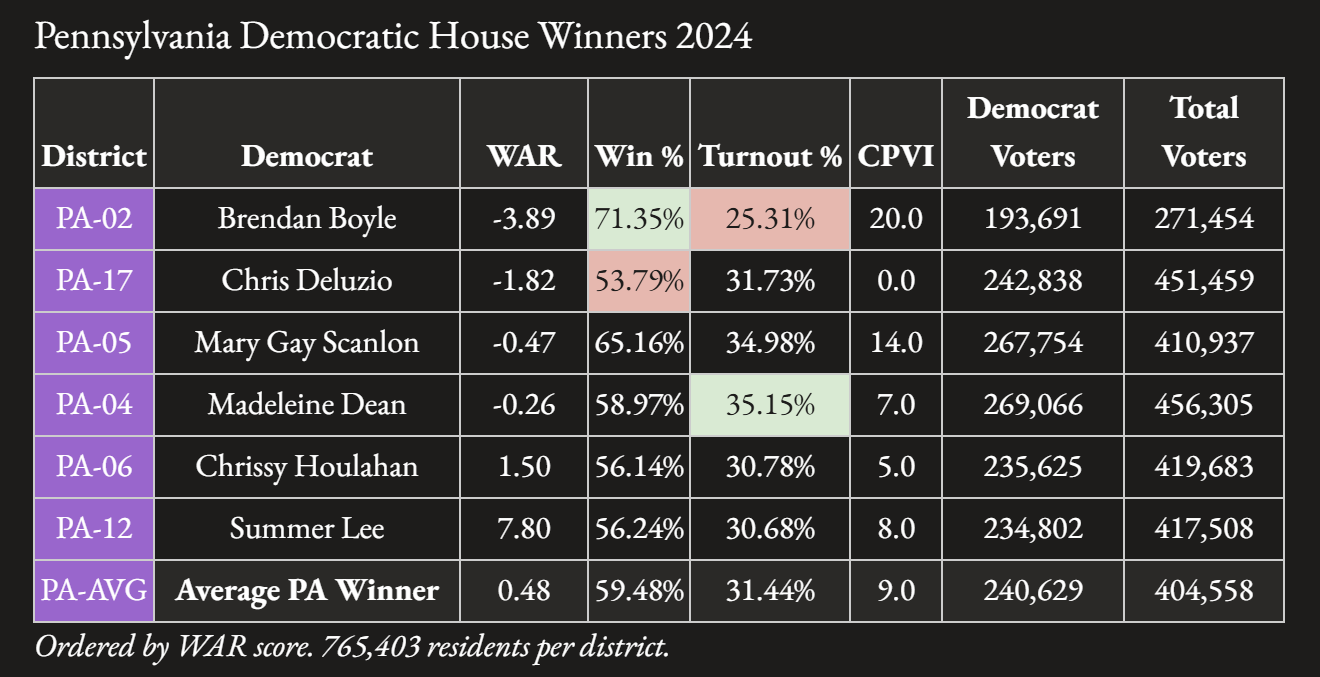

Laurel Resters

The second group of top WAR swing state candidates includes Pennsylvania, Arizona, and Wisconsin. Similar to the previous selection, these districts had the lowest turnout in their 2024 elections. In contrast to the previous states, these candidates come from districts with the most favorably partisan constituents, per the CPVI. In addition, they won their elections with the highest percentage of votes cast out of the winning Democrats in their state.

Working with an entirely different voter landscape, the candidates from PA-02, AZ-03, and WI-04 shared the same traits as the previous group in that they won via low turnout and high propensity voters. In the safest districts, it may not be too strange for the best Democratic candidates to have a lower total voter count, as the participation of their opposition may be diminished. However, the safest districts turning out the fewest Democratic voters is a red flag, particularly for those up the ticket.

I put the states in this group under the label “laurel resters.” These bastions of Democratic support should be areas where candidates can run up the numbers by either appealing to the base or turning out new voters by adopting views that motivate their local residents. By instead leaning into high propensity swing voters on their right, the candidates win elections at the expense of an ever growing oppositional sentiment from the wider populace.

Outside of these three swing states, Nevada follows a similar pattern without checking all the boxes to secure the label. Steven Horsford, for NV-04, has the top WAR, win percentage, and CPVI, though he is tied with another district for partisanship. Coming in the middle of three Democratic winners in terms of turnout, Horsford’s district is in line with the laurel resters, but perhaps he is not resting quite as much.

WAR, What Is It Good For?

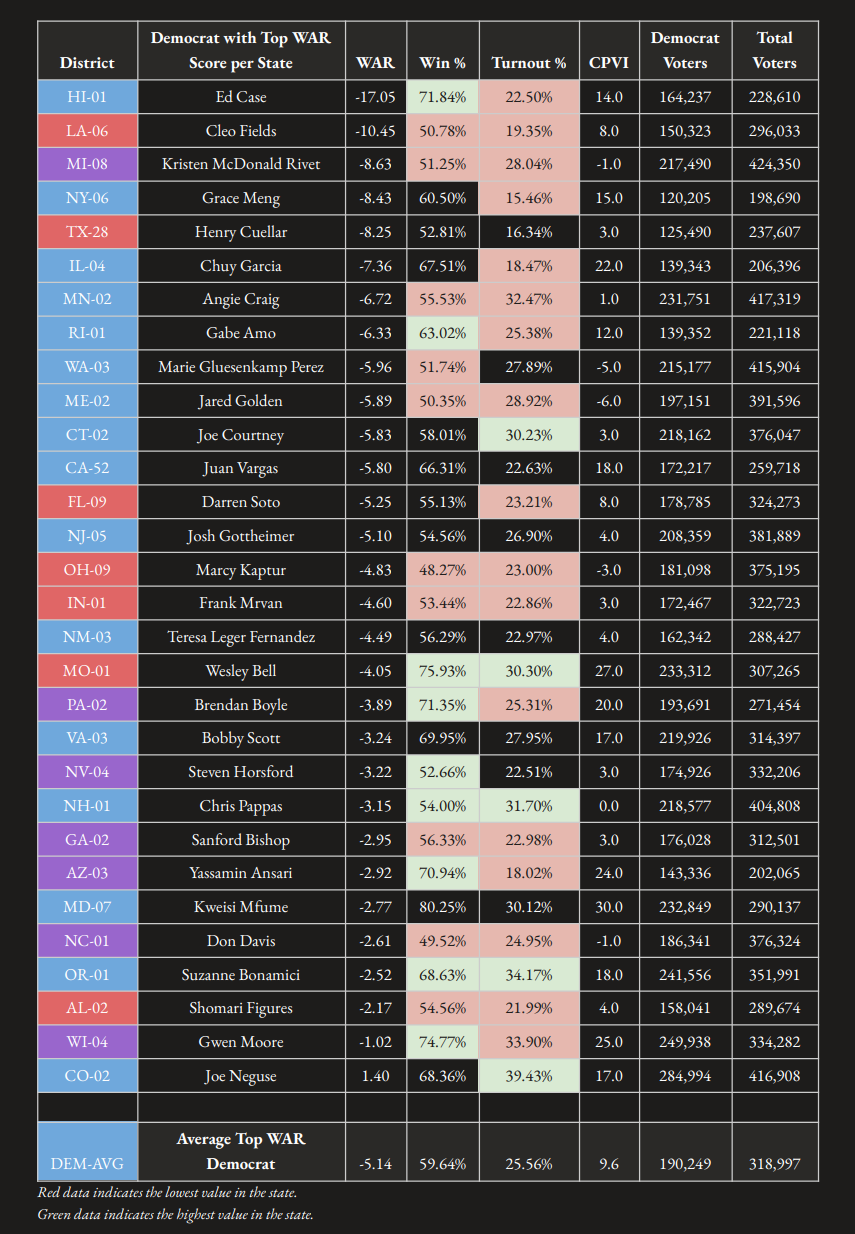

Thirty states have more than one Democrat with a calculated Wins Above Replacement (WAR) score from the 2024 elections in the House of Representatives. Charted above are the top performers in each state, according to their WAR value. Seventeen, or 56%, of these “highest quality” candidates come in at the very bottom of their state’s turnout percentage. In the same statistic, all but four, or 86%, of them fall below their state’s average.

In an election the Harris campaign spent running to the right, it makes sense that Democratic centrists, or swing district representatives in general, would outperform their progressive counterparts. When the presidential candidate embraces right wing positions or framing, they may bolster their down ballot performance with Republicans in purple or red districts but will weigh on the party in areas that rely on the base. To conclude that the candidates most successful under a losing strategy are the future model for the party is worse than short-sighted, given the tactic already failed on a national stage.

As a descriptive value, the WAR score helps paint a balanced picture of how politicians performed. The limit to the assessment’s prescriptive power lies in its assumption of a generic alternative and the reliance on the past status quo. A political party that sought urgent sweeping victory would not analyze districts won with 50% of the vote as inspirational and would instead seek to increase that number via appealing to the nonvoting populations that happen to be above average in size in the same areas. Should a candidate be replicated if they are so similar to the opposition that voters will gladly split their ticket?

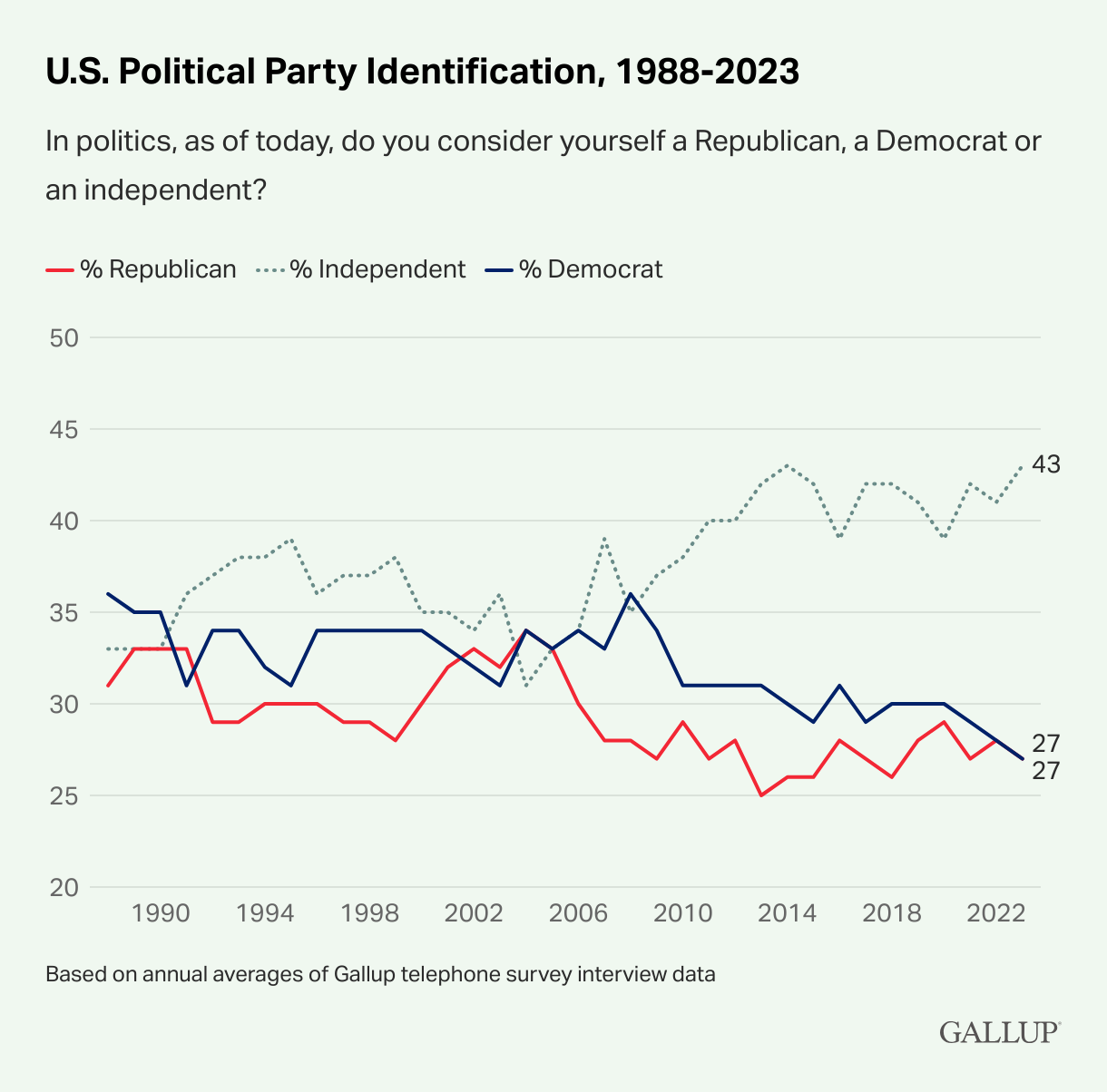

In the modern era, the American political conversation is not between the upper classes in the way the Democratic party seems to believe or perhaps wants it to be. The centrist swing voters are not a serious constituency to which can be consistently catered. Within the group, individual positions on almost any issue can vary wildly, and there is no inherent consistency. The lack of ideology leaves only abstract ideas, such as normalcy or stability, to which politicians can appeal. Some Republican voters can be brought under the Democratic umbrella, but they don’t have to be directly marketed, as they already share attributes with the massive, though draining, pool of nonvoters.

The goal going forward should be the working class coalition that every American politician pretends to have garnered since FDR, but for real this time. As voting numbers and anti-establishment tendencies both climb, the Democrats have found themselves in a situation where they need to see shifting to the right no longer gives the return on investment they previously believed it did. The party must adopt and champion bold policies that simultaneously benefit their base and motivate nonvoters, if it hopes to grow and compete.

Of course, the largest and most necessary policy decisions, from granting healthcare to labor and civil rights, are often the hardest to enact and require substantial political support and power. The Democrats need to focus on building a reformed party in the public eye and selecting impactful, practical goals. From large to small, there are plenty of ostensibly moderate, democracy-oriented movements into which the Democrats could invest energy.

Congresspeople should not be trading stocks. Lobbyists should not control the government. The representative from North Carolina’s 1st congressional district really should not be funded by groups advocating on behalf of the interest of foreign nations. Corporations and billionaires should not have control over our politics in any way. These problems have highly popular solutions and are only restrained by the power of money and greed at the highest levels of society across the political spectrum. The Democrats should abandon the money and embrace the people. For those scoffing, remember as long as we don’t state the obvious, they will feign ignorance.

Electoral college reform, gerrymandering relief, DC statehood, expansions for the House of Representatives and Supreme Court, among others, are all movements to increase the fairness and scope of American democracy. If Democrats want to be the popular party going forward, they should champion and publicize movements that increase the voice of the people and make big moves when they have the power to actually prove themselves to be receptive.

To start even smaller and further disconnected from any ideology, Democrats could build support by focusing on less consequential areas, such as just making Election Day a federal holiday. On the national stage, Democrats can and should be pointing out the disparities between blue and red states in simple areas, from internet censorship and marijuana criminalization, to right-to-work laws, there is plenty of unpopular governing happening in red states that could be highlighted to strengthen a national movement. These low hanging fruits are entry points into a diverse, working class coalition, which then must be strengthened with an actual ideology based on a bottom up perspective.

The future of the Democratic party may lie in the rounds of primary elections over the next few years. All sides should embrace a lively and high engagement process, as a key to fixing the turnout issue will be giving voters a say prior to the general election. This is critical on a local level, but even nationally, as the past three presidential primaries have been undeniable setbacks for the Democrats in terms of both energizing their base and appealing to the vast swaths of unreached voters.

To achieve a productive primary process, the Democrats need to root out billionaires and corporations from avenues of disruption. The goal of a real working class party, or any group dedicated to democracy, would be to eliminate these elements from American elections as a whole, and primaries are a prime place to start. Candidates with high WAR scores should embrace this reform to create a fair system, as they would be in position to benefit the most, since they are theoretically the most capable and quality politicians. Those districts, given their low turnouts, would also likely also be able to motivate more voters if they served their residents instead of corporations and billionaires.

Unless of course, they are not the most magnetic candidates thanks to their policies and charisma, but instead are the most adept at playing the game in a system built to benefit the wealthy and powerful. As long as the Democratic party rewards corporate-style ladder climbing and fundraising ability, the less likely they elect politicians with the motivations to make the systemic changes that their voters want.

The party must listen to more voices if they ever hope to serve them.